The reconstruction of phylogeny - How do we analyze the characters used in phylogenetic inference?

Homplasious characters

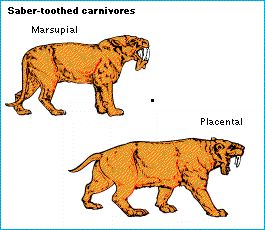

Convergence can be impressively deceptive. A classic example of convergence comes from the two major groups of mammals, the marsupials and placentals.

The marsupial and placental saber-toothed carnivores both evolved long, gashing canine teeth and there are striking similarities in skull shape and body form in the marsupial and placental wolves. If we inferred the phylogeny of the marsupial wolf, the placental wolf, and the kangaroo, from the pattern of phenetic similarity, we should obtain the wrong answer. The two wolves are phenetically more similar, even though the marsupial wolf is phylogenetically closer to the kangaroo than to the placental wolf. The phenetic similarity between the wolves is homoplasious and is not due to a close phylogenetic relationship.

Homoplasous characters do not reliably indicate phylogenetic relationships because they can fall into any grouping of species; they are not constrained to fall into phylogenetic groups. Different homoplasies can fall into different and conflicting groupings and the existence of homplasies is an important reason for conflict among characters.

The paleontologist Simon Conway Morris discusses the problem.

Figure: convergence in marsupial and placental carnivores. The reconstructed bodies of Thylacosmilus, a saber-toothed tiger that lived in South America in the Pliocene and of Smilodon, a saber-toothed placental carnivore from the Pleistocene in North America.

| Next |